What is tokenomics and how does it affect prices?

Tokenomics plays a key role in the functioning and development of any blockchain project that issues its cryptocurrency. It is a complex economic model that determines how digital tokens are created, distributed, and used within the ecosystem.

The quality of the tokenomics elaboration and its transparency for investors determines the project’s ability to attract capital for its development. Investors prefer to invest in cryptocurrencies with a clear and reliable economic model.

Contents

- Fundamentals of tokenomics

- Basic elements of tokenomics

- Impact of tokenomics on the price of cryptocurrency

- Tokenomics and long-term sustainability

- How to evaluate cryptocurrency tokenomics?

- Conclusion

Fundamentals of tokenomics

Definition of tokenomics

Tokenomics (token + economy) is a system of economic incentives and mechanisms determining how digital tokens are created, distributed, and used within a blockchain ecosystem.

In essence, tokenomics describes the internal economic model of a cryptocurrency project:

- Under what rules and in what quantity tokens are issued.

- How they are distributed among the various participants of the network.

- What functions they perform and what value they represent.

- What built-in mechanisms encourage holding and using these tokens.

Tokenomics has a huge impact on the value of a cryptocurrency, its growth prospects and attractiveness to investors. Well-designed tokenomics with transparent and balanced rules is the key to the viability of the project.

Key components of tokenomics

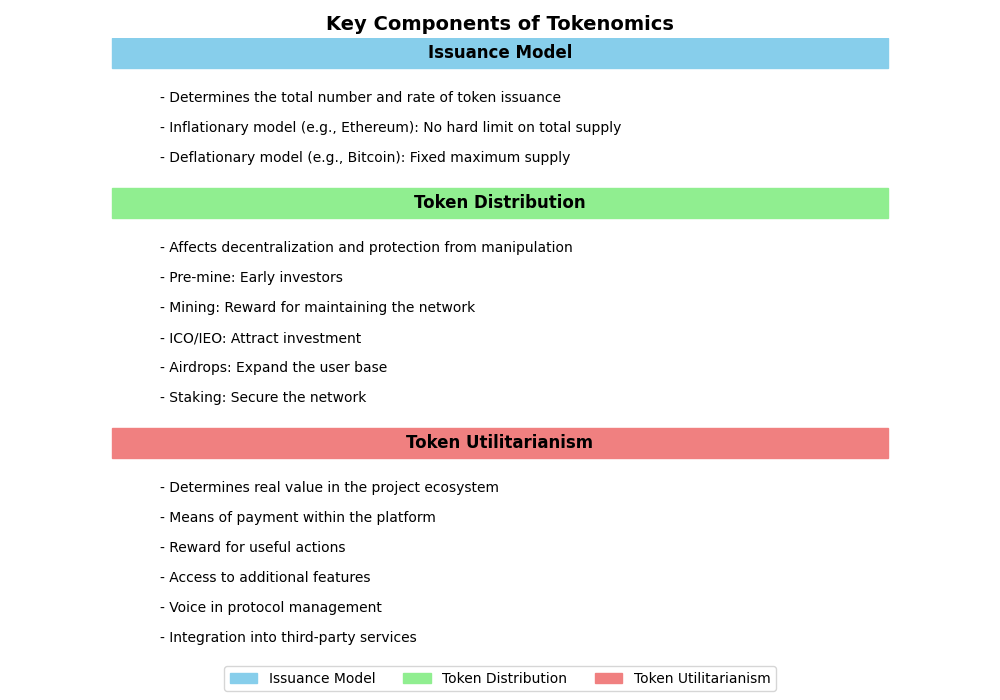

Let’s take a closer look at the main components of tokenomics, on which the success of any cryptocurrency depends:Tokenomics design is based on three key parameters.

The first is the issuance model, which determines the total number and rate of token issuance. In an inflationary model like Ethereum, there is no hard limit on the total supply of coins, whereas the deflationary model used in Bitcoin sets a fixed maximum volume of tokens.

The second parameter is token distribution, which affects the decentralization of the network and protection from manipulation by large holders. There are several distribution methods: pre-mine for early investors, mining as a reward for maintaining the network, ICO/IEO to attract investment, airdrops to expand the user base, and staking to secure the network.

The third parameter is the utilitarianism of tokens, which determines their real value in the project ecosystem. Tokens can be used as a means of payment within the platform, serve as a reward for useful actions, provide access to additional features, give a voice in protocol management, and be integrated into third-party services.

Difference between the tokenization of different cryptocurrencies

Using Bitcoin, Etherium and several popular DeFi projects as examples, let’s understand how their tokenomics differ:

| Cryptocurrency | Emission | Distribution Model | Utility |

| Bitcoin (BTC) | Limited – 21M BTC | Mining with gradual complexity increase and miner rewards halving every 4 years | Digital gold, store of value and medium of exchange |

| Ethereum (ETH) | Unlimited | Initial premining + mining ( transition to Proof-of-Stake) | Internal ecosystem currency for gas payments in transactions, development of smart contracts and ERC-20 tokens |

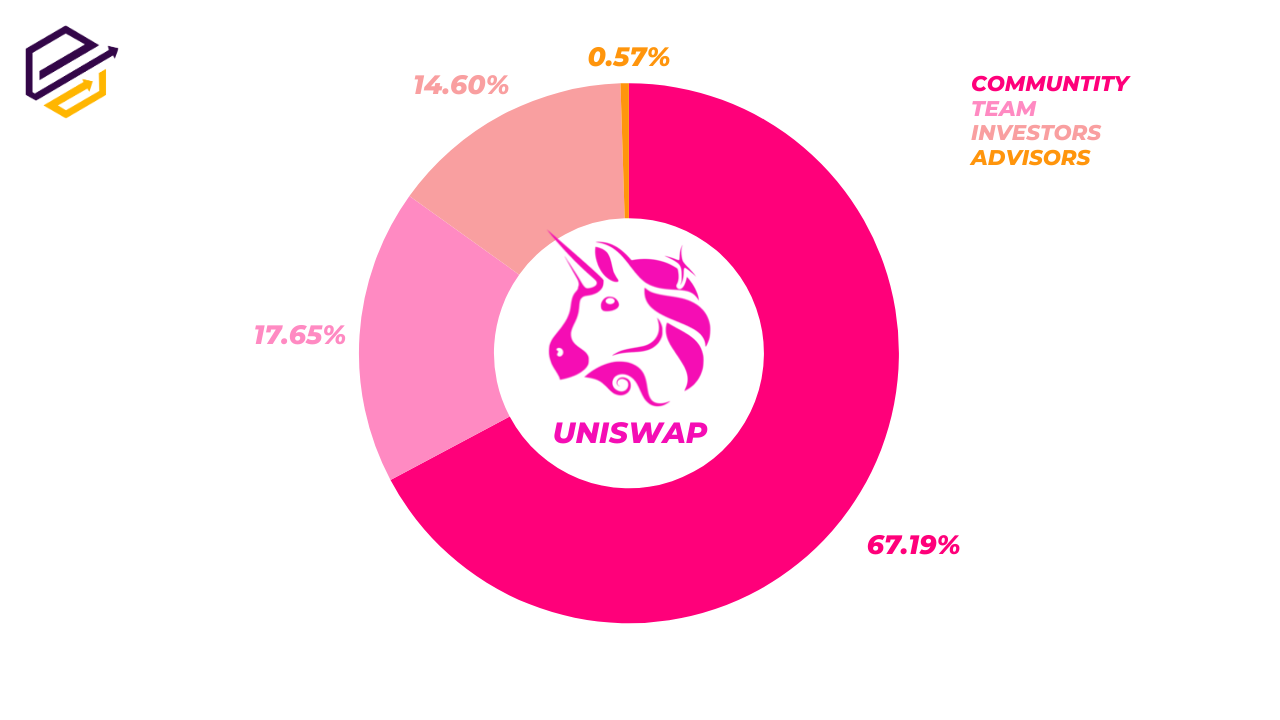

| Uniswap (UNI) | Fixed at 1B UNI, 60% distributed over 4 years | Retroactive airdrop to early users, rewards for liquidity providers, developer grants | Governance token, giving voting rights for protocol changes, grant distribution, etc. |

| Compound (COMP) | Unlimited, volume changes algorithmically | Rewards to users for providing crypto loans or borrowing | Right to vote on key decisions in Compound protocol governance |

We can see how diverse the issuance models, distribution mechanisms, and token utilization of different blockchain projects are. However, the key principles remain the same – limited resources, stimulating demand and creating utilitarian value.

Uniswap Tokenomics

Basic elements of tokenomics

Token issuance

Token issuance is the process of creating and circulating new units of cryptocurrency. The issuance policy determines how fast the supply of tokens on the market grows and how this affects their price. Key issues of issuance:

- What will be the maximum volume of tokens in circulation?

- At what speed and according to what schedule they will be issued.

- Who will be able to create new tokens and under what conditions.

The answers to these questions are embedded in the blockchain protocol when launched. A well-thought-out issuance strategy helps control inflation, create scarcity, and increase the value of cryptocurrency in the long term.

Limited or excess supply is the most important factor in pricing. Therefore, many projects initially fix the total number of tokens that will ever be issued.

This is done by analogy with commodity money like gold, whose reserves are limited by nature. Some projects refuse the upper limit of emission at all. This is what Ethereum developers did, leaving the supply of ETH theoretically infinite. However, I do not think that this devalues either – the complexity of mining limits its emission.

In each case, developers model the optimal volume of tokens, which will provide sufficient liquidity for the market and scarcity for price growth.

In terms of issuance approaches, all cryptocurrencies can be divided into two types:

Deflationary fixed-volume models:

- Hard-limited offer: the code limits the total number of tokens.

- Example – Bitcoin, Ripple, Litecoin, Cardano.

- Advantages – controlled inflation, growing scarcity, appreciation with demand.

- Disadvantages – risks of token loss, high volatility due to speculation.

Inflation models without strict constraints:

- There is no set upper limit on the number of tokens.

- Example – Ethereum, EOS, Stellar, Dogecoin.

- Advantages – scalability of the network, resistance to loss of tokens.

- Disadvantages – risks of excessive inflation and depreciation, necessity to burn tokens.

Issuance schedules differ, too. Bitcoin follows the halving model – halves the reward to miners every 4 years. Efirium, after switching to PoS, plans to issue no more than 1-2% of the total ETH turnover annually.

Mechanisms of token distribution

After issuance, how the tokens are distributed is crucial. If too narrow a group of investors receive them, centralization can lead to price manipulation. Conversely, a broad distribution supports decentralization and a fair ecosystem.

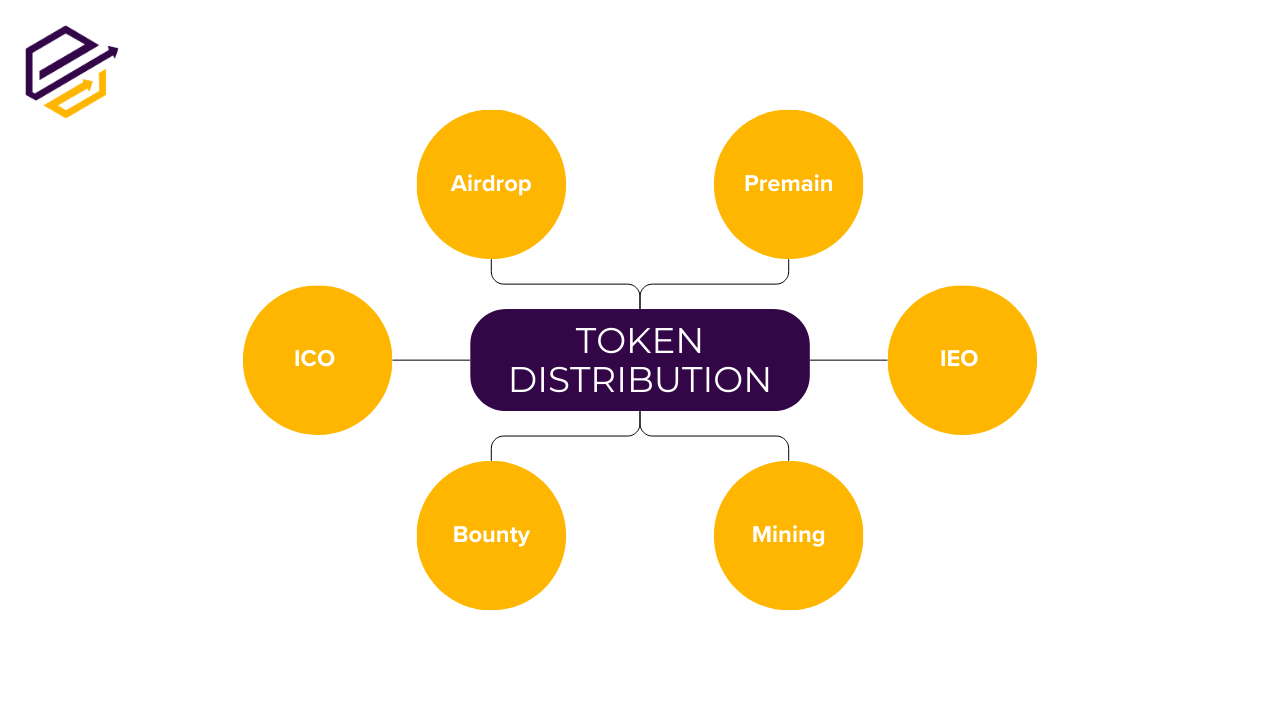

Projects use different methods to distribute tokens to primary holders:

- ICO (Initial Coin Offering) is an analog of an IPO in the crypto market. The project attracts investment in exchange for its tokens at a fixed price. Anyone can participate.

- IEO (Initial Exchange Offering) – similar to ICO, but the sale of tokens goes through a crypto exchange, which conducts the listing and takes a commission. This reduces the risks of fraud.

- Airdrop – free token distribution for simple actions (registration, subscription, repost). Helps to increase the recognition of the project and the number of holders.

- Premain – pre-release of some tokens before the public launch. They are distributed to the team, advisors, and early investors.

- Bounty – rewarding with tokens for helping the project (translation, bug-hunting, advertising in social networks).

- Mining – receiving tokens as a reward for computational work to support the network. This is how Bitcoin, Ethereum and other cryptocurrencies are mined using the PoW algorithm.

The availability of tokens after a project’s launch is a key liquidity factor. If a large share is in the hands of a few whales, there will be a shortage in the market. Therefore, adequate tokenomics assumes a fairly wide distribution with a limited share of individual holders. Even large investors get their tokens gradually through vesting – unlocking portions on a schedule.

In addition, the infrastructure itself for buying and selling tokens is essential. Listings on top exchanges and the availability of liquidity pools on DEX ensure the free circulation of cryptocurrency, reducing spreads between the buying and selling prices.

Allocation proportions between different groups of participants seriously affect the market balance. The higher the percentage of tokens sold on the open market, the higher the supply. Conversely, the stronger the initial concentration, the greater the artificial scarcity.

It is also important to consider lock-up periods for early investors. When their tokens are unlocked and enter the market, supply can rise sharply, and the price can collapse. Young projects are particularly susceptible to this.

The most stable projects are those with moderate pre-main (up to 20-30%), a generous public round (at least 30-50%), long-term vesting, and active community participation (bounties, airdrops). This model protects against speculative price manipulation.

Utilitarianism and application of tokens

In addition to speculative value determined by scarcity on the market, tokens acquire fundamental value due to their usefulness and relevance within the project ecosystem.

There are several typical mechanics of token utilization:

- Payment means – used to pay for goods and services within the platform (internal ecosystem currency).

- Voting rights – gives holders the ability to participate in the management of the protocol by voting for upgrades.

- Network resource – consumed as “fuel” to perform operations on the blockchain (gas on the Ethereum network).

- Functionality – provides access to additional premium features of the platform

- Staking – allows you to receive interest for long-term storage of tokens in the wallet or provision of liquidity.

- Collateral – serves as collateral for loans in DeFi protocols.

- Farming – distributed as a reward for liquidity providers in pools.

In the early days of the crypto market, project whitepapers were dominated by abstract “utility” tokens with no specific purpose. However, over time, investors began to pay more attention to actual use and natural demand.

The relationship between utility and price is best seen in the example of DeFi tokens. The more funds are embedded in the protocol (TVL) and the more frequent the transactions, the higher the value of the native token:

- Uniswap (UNI) is the main DEX token on Ethereum. Entitles you to a portion of commission revenue with a trading volume of $1 billion per day.

- Aave (AAVE) – token of the largest lending protocol with TVL over $6 bln. Used for steaking and commission discounts.

- PancakeSwap (CAKE) – token of the leading DEX on the Binance Smart Chain with up to $100 million in turnover per day. Used for pharming, lotteries, NFTs.

In projects with NFT, utility tokens often serve as non-interchangeable tokens themselves, which provide access to games and other features:

- Axie Infinity – NFT pets that are used in game battles.

- Decentraland – virtual plots of land in the meta-universe in the form of NFTs.

When dealing with tokenomics, it is important to separate utilitarian coins with natural demand from useless speculative tokens. The value of the former is supported by the project ecosystem, while the latter are rapidly depreciating to zero.

Staking and gratuities

Stacking is a passive income mechanism where the owner locks his tokens in a smart contract or wallet and gets rewarded for it in the form of new tokens. Depending on the protocol, steaking performs different functions:

- PoS consensus: token holders become validators and receive commissions for confirming transactions (Ethereum 2.0).

- Security: native token is blocked as collateral for reliable node operation (Cosmos, Polkadot).

- DeFi economics: the protocol encourages the provision of liquidity for exchanges and loans (Compound, SushiSwap).

The main effect of staking is to reduce the market supply of coins due to their long-term withdrawal from circulation. The higher the share of staked tokens, the less there are left to sell and the higher the price pressure.

Plus holders receive a stable interest income regardless of market fluctuations. This option makes the token more attractive for investment, which also pushes the price up.

Another way to manage the balance of supply and demand is to reward users with new tokens for activity or, conversely, to burn some tokens for certain actions. This redistributes value in favor of holders. Common reward options:

- Accrual of a percentage of exchange commissions to exchange token holders (BNB, FTT, HT).

- Airdrops, bounties and other rewards for loyalty to the project.

- Distribution of management tokens for staking in liquidity pools (UNI, SUSHI).

Examples of token burning:

- Buyback and burning tokens for a portion of the exchange’s profits (BNB, HT).

- Burning a portion of blockchain commissions when sending transactions (Ethereum EIP-1559).

- Burning management tokens when voting for protocol upgrades (MKR).

The effectiveness of these mechanisms strongly depends on the design of tokenomics and issuance parameters. If the rewards are too generous, inflation can offset the effect of burnup. Therefore, it is important to strike a balance.

Impact of tokenomics on the price of cryptocurrency

Supply and demand

One of the main factors governing cryptocurrency’s price is the market’s balance of supply and demand. When demand for cryptocurrency exceeds supply, the price rises as buyers are willing to pay more for the limited number of available coins. Conversely, when supply exceeds demand, the price falls as sellers are forced to lower the price to attract buyers.

Many cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin, have limited issuance. This limited supply creates scarcity and drives up prices in the long run, especially if demand grows.

Investment attractiveness

Transparent and economically sound tokenomics increase investor confidence and attract capital to the project. When investors see a clear plan for the issuance, distribution, and use of tokens, they can assess the cryptocurrency’s growth potential and make an informed investment decision.

Examples of successful tokenomics include Bitcoin, with its limited issuance; Ethereum, with its recently introduced mechanism for burning a portion of transaction fees (EIP-1559); and Binance Coin (BNB), with regular token burning. The elaborate tokenomics of these projects has contributed to the price growth of their cryptocurrencies, as investors believe in their long-term value.

Impact on liquidity and volatility

Tokenomics also affects cryptocurrency’s liquidity—the ability to buy and sell assets quickly and without a significant change in price. High liquidity means stable supply and demand in the market, which reduces price volatility.

Sophisticated tokenization mechanisms, such as listing on major exchanges, liquidity incentive programs (e.g., providing rewards to liquidity providers), and a large number of token holders, increase cryptocurrency’s liquidity. This, in turn, reduces the risk of sharp price fluctuations, as large transactions have less impact on the market.

Conversely, low liquidity can lead to increased price volatility. When trading volume is low, even relatively small transactions can significantly affect the price of a cryptocurrency, resulting in sharp spikes and drops.

Tokenomics and long-term sustainability

Properly designed tokenomics is a key factor contributing to a cryptocurrency project’s long-term sustainability and stability. A well-designed economic model helps to ensure a balanced ecosystem development, prevent manipulation, and create favorable conditions for token value growth.

However, improperly designed tokenomics can lead to serious problems and jeopardize the project’s long-term sustainability. One of the main risks is uncontrolled inflation, which arises from excessive token issuance. If the supply of tokens grows faster than the demand, it can lead to the depreciation of cryptocurrency and loss of investor confidence.

Another risk is the possibility of token supply manipulation. Suppose a significant portion of tokens are concentrated in the hands of a small group of individuals (e.g., developers or early investors). In that case, they can influence the cryptocurrency’s price by selling or buying large amounts of tokens. This creates instability in the market and undermines the credibility of the project.

An example of failed tokenomics can be seen in the BitConnect project. Its model implied high inflation, centralized token distribution, and a dubious reward scheme. As a result, the project became a pyramid scheme and collapsed, causing significant damage to investors.

How to evaluate cryptocurrency tokenomics?

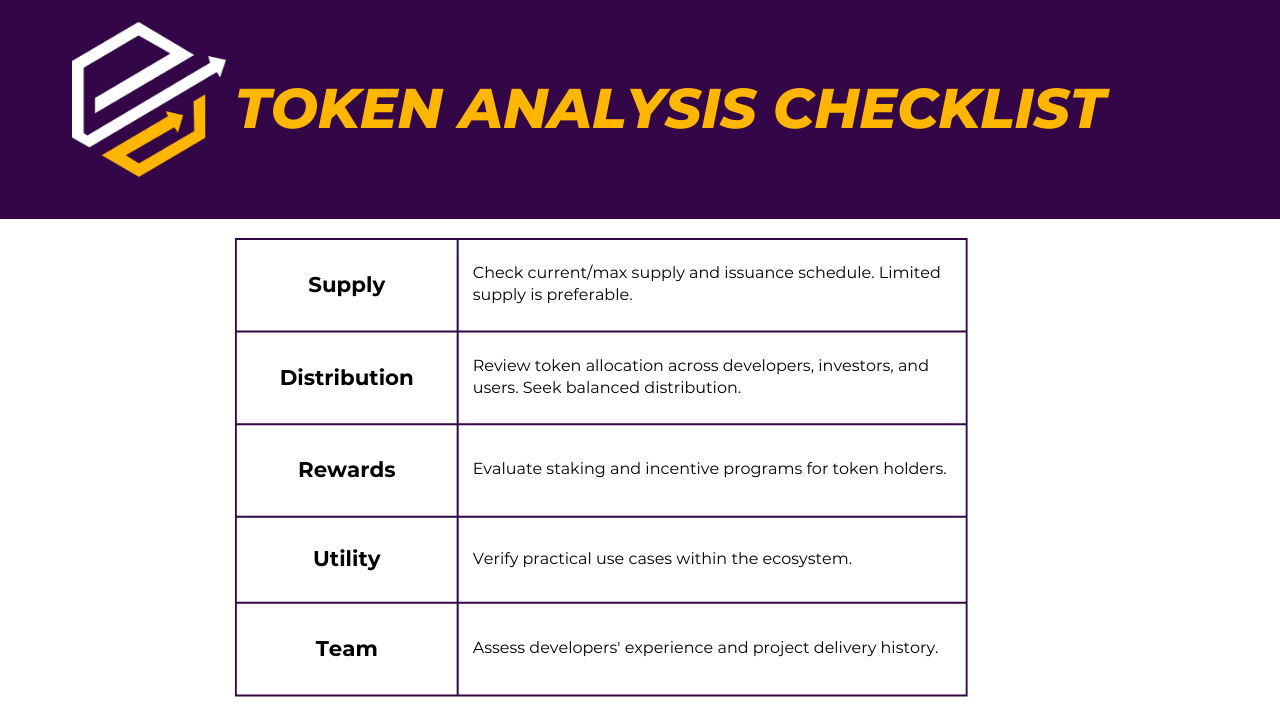

In order to make informed investment decisions, the tokenomics of a cryptocurrency project must be carefully analyzed. Several key factors should be taken into account when assessing the tokenomics:

- Token supply: Examine the current and future token supply, the issuance schedule, and the maximum number of tokens. A limited and predictable supply is usually a positive factor.

- Token distribution: Analyze how tokens are distributed among the different participants in the ecosystem (developers, investors, users). A fair and decentralized distribution reduces the risk of manipulation and increases the sustainability of the project.

- Reward mechanisms: Examine how the project incentivizes token holders and network participants. Well-designed reward mechanisms (e.g., stacking or loyalty programs) can increase demand for tokens and increase their value.

- Token utility: Assess the real utility and applicability of tokens in the project ecosystem. Tokens with a well-defined and sought-after utility have greater potential for growth and sustainability.

- Project team and reputation: Research the development team, their experience and reputation in the crypto industry. Check whether the project delivers on its promises and adheres to the stated tokenization model.

Conclusion

Tokenomics plays a key role in determining the value and sustainability of cryptocurrency. A well-designed economic model promotes balanced ecosystem development, attracts investors, and stimulates demand for tokens.

When assessing a cryptocurrency’s investment attractiveness, its tokenomics should be carefully analyzed, considering factors such as token supply and distribution, reward mechanisms, and utility in the project ecosystem.

Investors should favor cryptocurrencies with transparent, fair, and sustainable tokenomics. This will help minimize risks and maximize potential returns in the long run.